Regulatory Hurdles of a Revolutionary Technology to Fight Climate Change

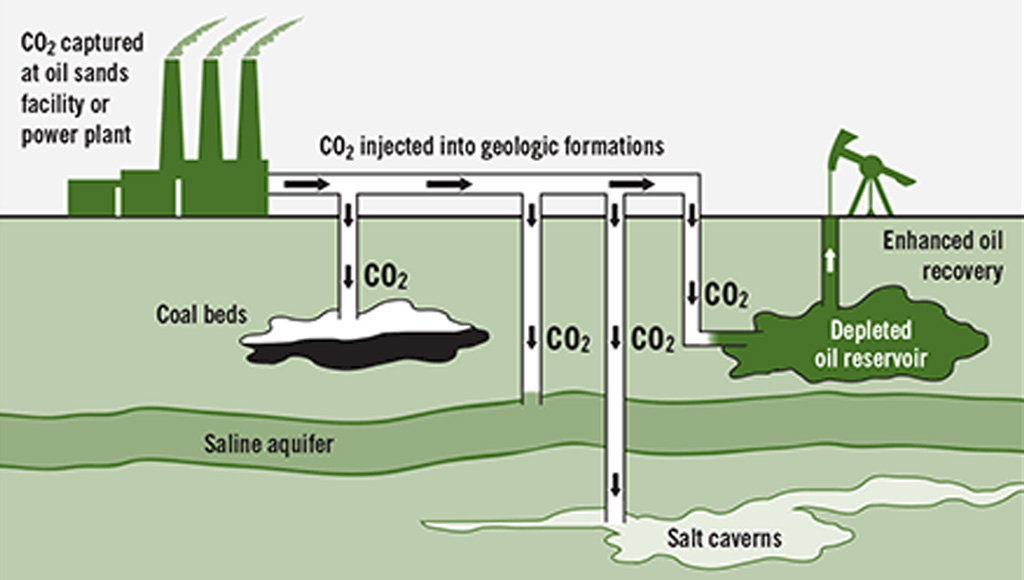

In the fight to minimize human-caused carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions associated with climate change, one of the latest and most exciting technologies is carbon capture and storage (CCS). The idea behind this method is that the CO2 emitted during certain activities, such as fracking for oil and gas, burning coal and natural gas for electricity, and many industrial activities such as ethanol production, can be captured instead of being released into the atmosphere. Once captured, the CO2 can be compressed into a denser gas or liquid and then transported by pipeline and used for enhanced oil recovery or permanently stored underground in saline aquifers, coal beds, salt caverns, or other geological formations. While the technology for capturing, condensing, transporting, and ultimately injecting CO2 has advanced notably in recent years to make the technology theoretically viable on a large scale, the actual implementation of the practice has lagged behind largely due to the regulatory hurdles associated with the transport and storage of the CO2.

Regulatory hurdles surrounding the transport and storage of CO2 are holding the technology back. New legal and regulatory frameworks are needed to ensure that the transport and storage of CO2 is done in a manner that is safe and effective, because CCS will fail to get off the ground as a climate mitigation strategy without such assurances. The issue, though, is the various hurdles these regulations bring that make the process more difficult, lengthy, and costly and could be restricting the demonstration and deployment of the technology before it can really get off the ground. Some of the chief regulatory hurdles include the following:

- Property rights: The property rights at CO2 storage sites are a critical part of the operation, including the property rights of the surface, the subsurface, and the pore space, as well as the question of how these property rights can be transferred between parties. In the United States, the standard process is one where the owners of the surface of the land retain ownership of the pore space into which the CO2 gets injected, receiving compensation from the operator injecting the CO2 for the right to use that space. However, U.S. regulations tends to give mineral rights primacy over CO2 storage rights, meaning that any oil, gas, or other mineral formations that are already established on that land take precedence. Such disconnect leads to the situations like the one in Texas that requires CO2 injectors to prove that it will not endanger any such mineral formations. Other states have started to legislate that the pore space that belongs to the owner of the surface property can be transferred to the operator, while others still say it cannot be transferred but only leased to the operator. This hodgepodge of regulations in different states leads to confusion and uncertainty in the injection process, not to mention legal challenges from property owners, all of which serve to delay and add extra cost burdens to the process.

- CO2 storage permitting process: Beyond just securing the property rights, further legal hurdles placed in front of CCS operators include the permits required by the government to ensure that sites are complying with regulations and projects do not negatively impact public health, the environment, or general safety. The challenge for operators, though, is that the permitting process can often be vague and unclear, especially in states that simply rely on their existing oil and gas drilling regulations to apply to CO2 storage instead of targeting the regulations for this specific purpose. As a result, the permitting process can take much longer than operators would like, to the point that the delay could result in the economics of the project changing drastically enough that it is no longer viable (as happened with the Tenaska Taylorville project). Additionally, as with the property rights regulations, the patchwork of varying laws across different states creates uncertainty and challenges for operators that would not be the case if there was a unified national policy.

- Liability and monitoring: A key aspect to the viability of CO2 storage projects is the long-term liability and costs once the CO2 has been injected. Oftentimes, the operator will be responsible for monitoring and ensuring that the site is still effectively storing the CO2 for a set number of years before responsibility for the site shifts to a regulatory authority of the state (for example, Illinois assumes liability once the storage site is officially closed and Montana accepts liability after the operator completes 30 years of monitoring). Some states, such as Kansas, never assume liability for a CO2 storage site. Further, there is no clear consensus on exactly how the storage sites are to be monitored or how operators are to prove that the CO2 is permanently contained. The long monitoring periods and the uncertainty behind how long operators will be liable ultimately increase the costs of CCS as a strategy and make the decision-making process more difficult.

- Financial securities: Related to the issues of liability and monitoring, operators of storage sites are often required to prove to regulators that they have enough funding built in for the long monitoring process, with the EPA requiring 50 years of site monitoring and demonstration of financial reliability every six years. With all the uncertainties regarding how the regulation of CO2 storage sites will unfold, operators are finding it tougher and tougher to provide assurances of such financial securities as they do not know exactly how much funding they should budget for monitoring and liability.

- Other issues: A host of other regulatory hurdles exist for the transportation and storage of CO2. Regarding the transportation of CO2, which is largely done by pipeline, the permitting process for building those pipelines can be as, or more, arduous as the permitting process for the storage sites. When it comes to the storage sites, complications arise when the CO2 injections end up crossing state lines or when Enhanced Oil Recovery (EOR) sites are converted to using CO2 for oil production, as the EPA has much stricter requirements for CO2 injections.

These issues further serve to increase the uncertainty and costs associated with CO2 storage projects, and add hurdles that impede the effective deployment of carbon capture, transport, and storage as a strategy for emissions reductions. Setting up a framework now is critical for CCS technologies to be used on a nationwide scale to meet climate and environmental goals. Regulation has progressed in the past decade, but much more slowly than is necessary to get this crucial technology to be widely implemented and allow the country to truly harness its potential.

Contact us to learn about how OnLocation can help you explore issues related to energy and emerging technologies.